As We Heal Our Warriors, We Heal Our Nation

- laurel539

- Aug 1, 2022

- 3 min read

A few years ago, I became very interested in the comparison of our modern-day military warfighter to that of past civilizations. Most importantly, how did they reintegrate into their society once a war or campaign was finished? All cultures, past and present, had warriors to protect and provide for the culture, clan, tribe, or country in which they are a part of. Additionally, many of these past societies recorded stories of rituals that the warrior was subjected to for the purpose of helping them recover from combat and guide them back into the daily cycle of life.

In these past societies, a warrior was not viewed the same as a soldier today; not merely a member of a huge military institution used to execute policy toward political ends. Instead, a warrior was one of the foundational roles that kept societies strong and functioning. Warriors were seen as protectors, not merely destroyers. In essence, there were basically three major classes within any society: the ruling class, the general citizenry, and the warrior class.

Today, however, the warrior is not valued or recognized as a social class. Our modern “warriors” or military members are generally viewed as members of a profession of arms, as that of any other profession within society. The principal difference being the level of individual risk to life, limb, and security.

Unfortunately, the violence and horror of war does not stay on foreign fields of battle once the warrior returns home. As Edward Tick explains in his article Heal The Warrior, Heal The Country, “War poisons the spirit, and warriors return tainted. This is why, among Native Americans, Zulu, Buddhist, ancient Israeli, and other traditional cultures, returning warriors were put through significant rituals of purification before re-entering their families and communities. Traditional cultures recognized that unpurified warriors could, in fact, be dangerous. The absence of these rituals in modern society helps explain why suicide, homicide, and other destructive acts are more common among veterans.”

Many believe that effects of war such as trauma or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) arose with modern mechanized warfare. Terms like “shell shock” from the first World War was not the genesis of PTSD. In fact, PTSD and the emotional effects are as old as war itself as revealed by many ancient texts. There are numerous written accounts of how these various cultures such as Romans, Greeks, Assyrians, Israelites, Spartans, Athenians, and others accommodated this “cleansing,” but one additional factor must be noted when reviewing how well warriors re-enter society. They must first believe the cause of the fight is just.

Consider the record of Deuteronomy 7:2, whereby the Israelites are commanded, “When the Lord your God delivers [the Canaanites] over to you, you shall conquer them and utterly destroy them. You shall make no covenant with them nor show mercy to them.” I’m confident that those who destroyed everyone in their path without mercy, could only do so if they truly believed in the righteousness of the act and the authority from which it came.

It has been recorded time and again that ancient warriors found peace with their actions in war if they believed the cause was justified and sanctioned by the society they fought for. Does this totally absolve actions within a warrior’s mind? In my experience, no, but it does help. After all, memory is almost impossible to erase but it can become less prominent over time.

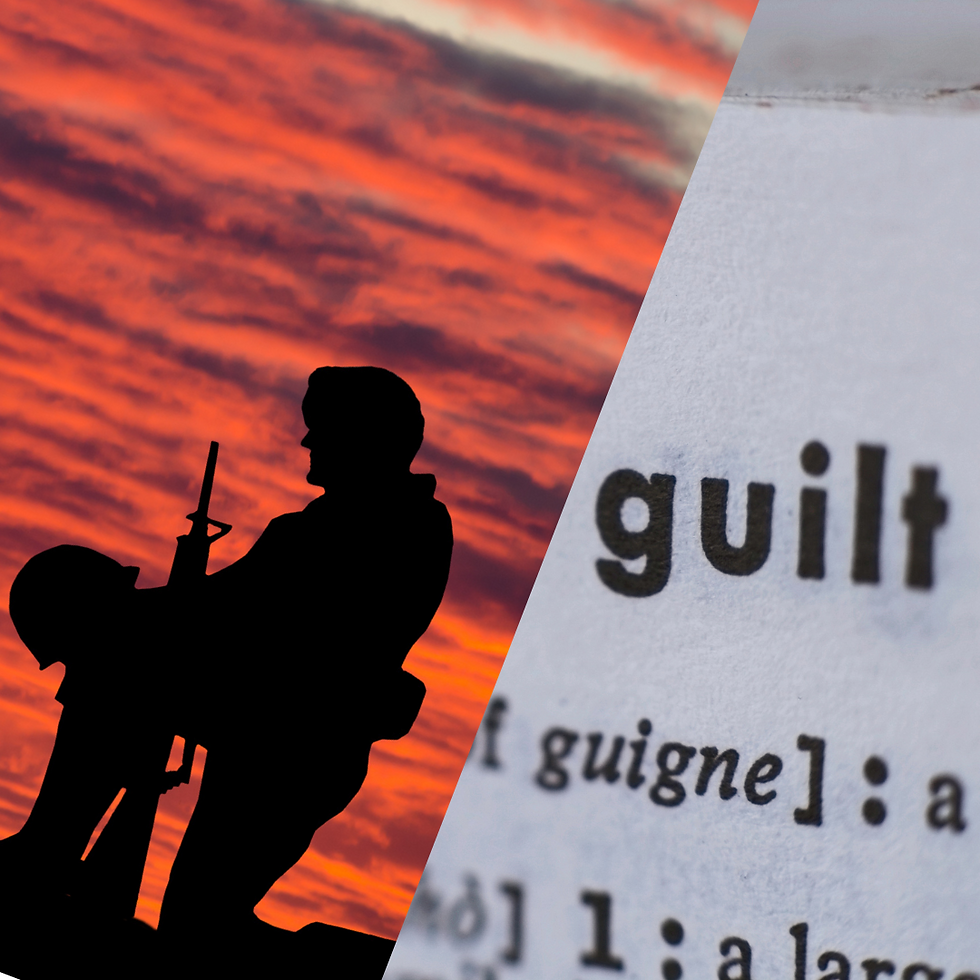

Together, as a society we can help to ease the feelings of loss, grief, and guilt within those we send to protect our nation. Let’s not forget that our society has a duty and responsibility to help these warriors resolve injuries both seen and unseen. And welcome them home regardless of politics.

“My past is an armor I cannot take off, no matter how many times you tell me the war is over.” - unknown

Comentarios